Martin Scorsese’s new Netflix documentary about Bob Dylan presents previously unreleased concert footage of the 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue. Baffling with its surreal atmosphere and narrative wit, the film is as much a product belonging to Dylan’s legacy as it is about his legacy.

By Max Rauser

Picture: via Flickr by Alberto Cabello, CC BY 2.0

In June 2019, Netflix released a new Bob Dylan documentary by director Martin Scorsese, who already directed No Direction Home, covering the first years of Dylan’s career in 2005. This new film focusses on a concert tour Dylan went on in 1975 and 1976: the Rolling Thunder Revue. But what makes this tour important enough to dedicate an entire film to it? How does it tie in with Dylan’s career as a whole? Might there even be secrets about this part of Dylan’s career left to uncover?

The scene is set with images of Bicentennial festivities: as if in a strange carnival, Lincoln, Uncle Sam and parades with gymnasts and guitar players pass the camera. Richard Nixon tries to conjure the American Dream in an attempt to unify a nation that is on the verge of breaking apart and feels humiliated after losing the war in Vietnam. Ginsberg recalls, »rumor came ‘round, that the inspired Dylan was back.« In this climate, Dylan develops the idea for a new concert tour. He gathers ‘round friends and musicians (the film introduces its characters), rehearsals take place and then the busses roll – with Dylan at the wheel. The Bicentennial carnival is replaced by a carnival on the concert stage.

The film narrates its story on three intertwined time levels. On the first level, there are interviews and especially concert and backstage footage from 1975. Much of this material has previously been unreleased and offers an exciting insight in the atmosphere of the tour and the cultural climate surrounding it. Building on this, there are two levels of retrospection. One comprises 2019 interviews with people who were involved in the tour and look back on it now. Among them are Dylan himself, Joan Baez, musicians and staff of the tour, the filmmaker Steve van Dorp and the journalist Larry Sloman. The third time level provides interviews with members of the tour who are already deceased by way of archive material spanning the time between 1975 and 2019. Therefore, the likes of Allen Ginsberg, Sam Shepard or Rubin Carter can also share their impressions.

Sloman and van Dorp

Multiple narrators structure the documentary with their memories in 2019. Two especially important ones are Larry ›Ratso‹ Sloman and Steve van Dorp, young men who covered the tour in 1975 – one by writing and the other by filming. They are part of a big group of artists traveling with the Revue, but due to their respective projects, they also reflect on the atmosphere and proceedings from an outsider’s point of view. They move between involvement and spectatorship, providing the viewer with a kind of window into the inner workings of Dylan’s tour.

Sloman is a young journalist who travels with the musicians to report for Rolling Stone. In many scenes of the movie, he is seen interviewing artists, roadies, and fans. The second perspective is that of young filmmaker Steve van Dorp, who autonomously decides to come on tour and record the proceedings. His footage of the concerts and the backstage atmosphere makes up the largest part of the documentary. In a 2019 interview, van Dorp – today wearing a Mohawk haircut and looking grim – goes on about his ›rival‹ Sloman, who allegedly was trying to appear and talk like Dylan. »He didn’t want anyone else with vision around,« van Dorp gripes. It is remarkable how Scorsese manages to bind disparate (and, in this case, sometimes rivaling) strands and snippets together to form a coherent narrative. Although Ginsberg, for example, is long deceased, interview bits with him serve as a narrative corner stone. Ghosts of the past rise, together with voices that are still alive, to give testimony of an artistic project young and fresh in the ‘70s.

The Tour

The Rolling Thunder Revue was different from every tour that Dylan had done before: he gathered a host of partly well-known, partly underground artists and booked small and intimate venues. On stage, they presented their own songs alongside his, while not only musicians but all sorts of artists worked on several projects together. Everyone wore make-up or dressed up in fantastic costumes. The tour’s next stop was often held secret for as long as possible, adding another layer to the mystery.

The year before, Dylan had gone on a big comeback tour with The Band to promote his Planet Waves album after several years of stage absence. He had sold out arenas. The Rolling Thunder Revue was distinctly different in character. Dylan’s idea »was to put a tour up, a combination of different acts on the same stage for a variety of musical styles.« This stage was crowded: Dylan, Bob Neuwirth, T-Bone Burnett and Mick Ronson were all playing the guitar, to name only the »cast« for one instrument. Roger McGuinn, Joan Baez or Joni Mitchell among others would sometimes join them. Musicians would come and perform one or two concerts in certain cities and drop off again. Some, like Mitchell, were so intrigued by the communal atmosphere that they stayed for the rest of the tour.

Next to the musicians, there were writers on board. Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and his partner Peter Orlovsky as well as their associate Anne Waldman traveled around with the tour, read poetry on stage, served as roadies and organized meditation sessions in hotel rooms. The film shows Dylan taking the playwright Sam Shepard along to collaborate with van Dorp. In 2019, Dylan attributes a special »knowledge of the underworld« to Shepard, an ability to »commune with the dead« that he thought could help van Dorp in making his movie. Dylan does not elaborate, but since Shepard died in 2017, the interview sections with him now are a communication with the dead themselves. Maybe Dylan’s remark should be understood as a commentary on this fact.

»Hurricane«

The tour also provided the context for Dylan to somewhat return to his protest song roots. Not only does a long section of the movie focus on an intense rendition of Dylan’s mid-60s song »The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carrol«, but he is also shown singing Peter La Farge’s »Ballad of Ira Hayes« at the Tuscarora Indian Reservation. Ira Hayes, a Native American soldier in WWII, is a symbol for the USA’s failures in dealing with its Native American population. On tour, Dylan wrote the song »Hurricane« about the African American boxer Rubin Carter, who served time in prison for allegedly murdering three white people in a New Jersey bar in 1966. The trial, however, was based on scanty evidence, and after Dylan’s song maintained Carter’s innocence, he was acquitted in 1985. The biggest concert of the Rolling Thunder Revue was performed in January 1976 in Houston as a benefit concert for Carter.

Although political and social criticism is a part of Dylan’s songwriting that comes up in several songs throughout his career (after 1975 for example »Union Sundown« on Infidels (1983) or »Political World« on Oh, Mercy (1989)), so-called »protest songs« never became nearly as central to his music again as they were on his first folk albums. Since 1964, Dylan had distanced himself artistically from overtly political songs, and »Hurricane« remains probably the most influential of a few exceptions.

Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Persona

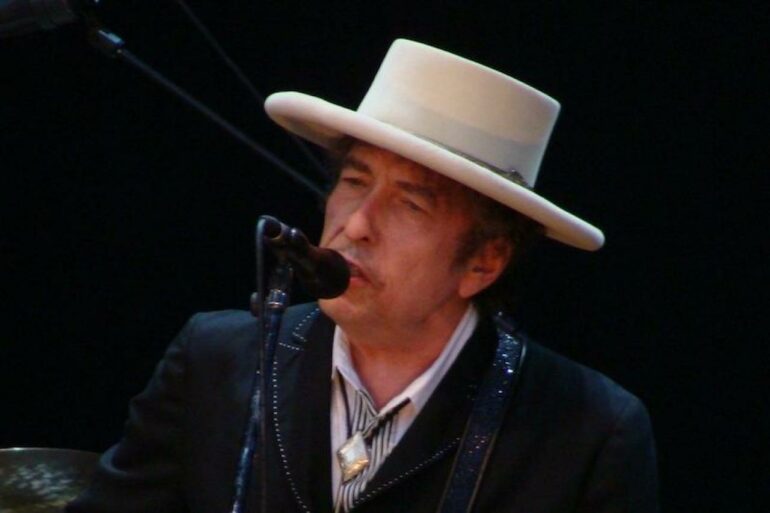

When he went on the road in 1975, Dylan’s public image was still influenced by his latest albums and the ‘74 tour: a healthily round-in-the-face, well shaved performer. His Rolling Thunder Persona, though, was all extravaganza. The movie shows him in vests and scarfs, with eyeliner, white paint in the face and wearing a big hat with peacock feathers in the hatband. His blue eyes gleam dangerously, his hair is long, his beard unkempt and his face seems haggard if it can be seen at all – while Dylan had only joked that he had his »Bob Dylan mask on« in 1964, the mask became his definitive accessory on the Rolling Thunder tour eleven years later. In addition to the make-up, concert footage shows him even singing through a plastic mask. In other instances, two Dylans stand on stage, astonishing the crowds – Joan Baez is dressed up as him. The 2019 Dylan carries it even further: »We didn’t have enough masks on that tour. We should have had masks for everybody.«

This 2019 Dylan has become very old. He is dressed like a Southern Gentleman, wearing a black shirt and a bolo tie with a turquoise stone. Most of the time he does not look into the camera but rather seems to be searching inwardly for memories. He gives calculated and concise statements. One of the greatest moments of the documentary is when he seems to let his façade slip and claims he would not remember anything about Rolling Thunder. This scene is set up in a comical way: The background music suddenly stops, and Dylan angrily complains about his failing memory. After having watched the whole movie, one wonders if there is not another mask waiting behind the façade.

Joan Baez reunited with Dylan publicly on this tour. In interviews, she remembers the atmosphere to be liberating. Finally, she could break out of her own stage persona and take up an entirely new, rebellious role. On stage, she could flirt with him and dance wildly to guitar solos. No trace was left of the pristine voice and the subtle but intricate guitar arrangements normally associated with her. »There was a Rolling Thunder energy,« she says in 2019. »It was his invention and all these people showed up.« In an emblematic shot of the film, the Rolling Thunder Dylan dances up a small sandy hill. With a trumpet in his hands, he leads a queue of people, probably members of the tour, who sing and follow him. He looks like the Pied Piper leading his followers into his world.

The viewers also get a – maybe unpleasant – taste of the private Dylan: A scene from 1975 shows him and Baez reminiscing in a bar about their former romantic relationship. Both talk so intimately, swaying between flirting and calmly accusing each other of emotional betrayals, that one is caught between awkwardness and voyeuristic interest. It seems strange to have such a conversation filmed.

Show Business

The film follows several links between the tour and its pop cultural context in a casual, anecdotal style. Among the stories are some astounding revelations, even for Dylan aficionados. For example, Sharon Stone remembers meeting Dylan after a show she had attended as a fan. She was not yet an actress but already pursued a modelling career, and after Dylan had seen her, he played »Just Like A Woman« and invited her to come on the tour. She did and took responsibility for the costumes of the performers.

Dylan’s white face paint is revealed to have been inspired by the make-up of legendary rock band KISS. His violinist Scarlet Rivera was in a relationship with the singer Paul Stanley and had taken Dylan to a concert of the band. Rivera is maybe the most fascinating character of the whole tour, painting her face with imaginative patterns before every show and dressing up in elaborate costumes. Apparently, she wore a sword and had a snake with her on tour.

Guitarist Mick Ronson exemplified the glamorous character of the Revue as much as Rivera did. He was recruited from David Bowie’s former live band The Spiders from Mars. No other phase in Dylan’s career comes as close to the campy glam rock era of Pop music that started in the seventies in the UK as the Rolling Thunder Revue does. It is only natural that Ronson, being one of the subtle protagonists of that era, also featured in the Rolling Thunder live shows although he claimed that Dylan never really spoke to him.

The Twist

Carnival atmosphere and an air of mystery surround the concerts. Show and performance is everything and nothing seems as it is. Scorsese reproduces this feeling: there are some inconsistencies, some questions the viewers are left with after watching his film. Why does it end with a snippet of a man putting a mask on? Why are the credits overwritten with the words »The Players«? Why are the people who were interviewed associated with roles? Allen Ginsberg features as »The Oracle of Delphi«, Baez as »The Balladeer«, Sam Shepard as »The Writer« – while this can still be taken as a simple joke adding to the atmosphere, it gets confusing when not Steve van Dorp is credited with »The Filmmaker«, but ›Martin von Haselberg‹. Upon researching this von Haselberg, it turns out that some of the most interesting facts in the documentary are simply made up. The whole film – dressing up like a documentary – has all along told invented stories intertwined with actual ›truths‹.

Martin Scorsese

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese

Netflix / Grey Water Park Productions & Sikelia Productions 2019

142 minutes

Steve van Dorp, to start with, does not exist. He is a fictional character and played by performance artist Martin von Haselberg. He did not record any of the material of the 1975 concerts. The images that serve as the basis of the film are made up of real concert footage and scripted scenes. Both were originally meant for Dylan’s movie Renaldo and Clara, which he wrote and directed together with Sam Shepard. It was released in 1978 but never distributed on DVD and is to date only available in excerpts. Van Dorp’s name and voice have been inserted into the videos in post-production. The anecdotes about Sharon Stone and KISS are equally fictitious. Stone neither met Dylan in 1975 nor did she join the tour as a staff member. Likewise, Rivera did not take Dylan to a KISS concert. The idea for his face-painting most likely came from the movie Les Enfants du paradis. The heartbreaking conversation between Dylan and Baez was not spied upon by a ruthless camera man. Instead, they were acting out a scripted scene for Renaldo and Clara.

The film, however, is neither a joke nor a conventional mockumentary. The masquerade that the movie presents is a guiding principle of Dylan’s (more recent) work: his autobiography Chronicles: Volume One, published in 2004, has been called out by critics for presenting partly fictitious accounts of Dylan’s life. His newer songs consist of quotes from all kinds of different sources. Even the original movie Renaldo and Clara merges facts about Dylan’s career and real concert footage with fictitious scenes and characters.

Scorsese may not at all times tell the factual story of the Rolling Thunder Revue, but he conjures its spirit, as is said in the beginning of the film. Because the mask as a principle is so much part of the tour and of Bob Dylan’s work, Scorsese cannot present the audience with the actual facts if he wants to genuinely convey the gist of his topic. As Dylan says: »When somebody’s wearing a mask, he’s going to tell you the truth.« – and maybe only then.