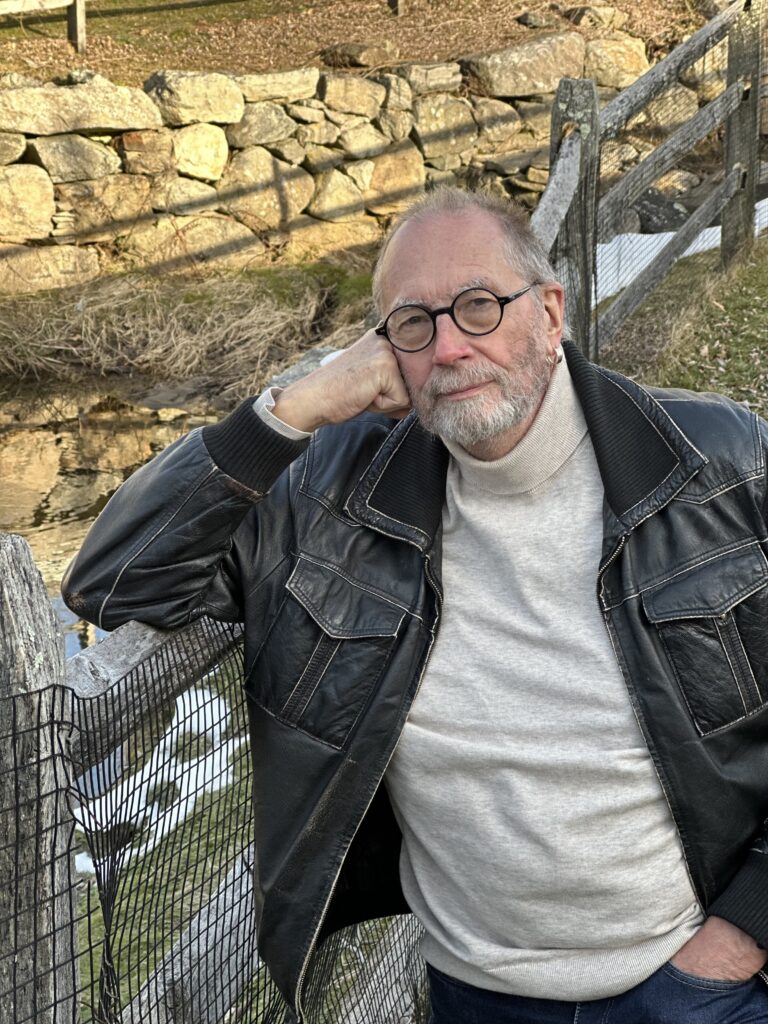

Philosopher Graham Priest talks about the Western orthodoxy in logic and his view of dialetheism. He denies that there is any noteworthy connection between logic and political philosophy. An interview on logic, capitalist ideology, and the question: How can we move the world to a better place?

Interview by Frederik Eicks

Picture: Penrose triangle, via Wikipedia, Public Domain

First off, what is one even doing when they philosophise?

I wouldn’t try to define philosophy because the question ›What is philosophy?‹ is itself a philosophical question, and any answer is going to be contentious. So, when people ask me what philosophy is, I tend to give them typical examples of philosophical questions, like: What’s the nature of reality? How do you run the state? How should I live? How do you know any of these things? (Of course, when you answer questions like that, many more esoteric questions that tend to be involved in answering those big questions will also come up.) Taking into account what people have said before, you give reasons, you try to answer objections, and you try to find an answer that satisfies at least you, if not everybody.

You are most renowned for your works in logic, particularly for your view of dialetheism, which concerns contradictions. What is a contradiction, and how does dialetheism come into play?

The word ›contradiction‹ has many possible meanings, but logicians tend to use it in a very precise sense. Namely, it’s a statement of the form ›So-and-so, and it’s not the case that so-and-so‹. For example, it’s raining and it’s not raining. This is kind of a simple case, of course, but essentially a contradiction is something of the form ›p and not-p‹, as logicians would write it. And a dialetheia is something of that form which is true. It’s high orthodoxy in Western philosophy that nothing of that form can be true. Dialetheism is, shall we say, an unorthodox view.

What is an example of a true contradiction?

A number of possible examples of these have been given over the last 40 years or so. The one that’s got the most airtime concerns the paradox of self-reference, e.g. the liar paradox. The liar sentence is a sentence of the form ›This sentence is not true‹. With a little bit of reasoning, which is very straightforward, you appear to be able to establish that it’s both true and not true. And if that’s right, then, of course, that is a dialetheia.

You mentioned the Western orthodoxy when it comes to contradictions. Are we, at least in the Western world, obsessed with contradictions?

Maybe obsessed is not the right word; but an abhorrence of contradictions is highly orthodox, certainly. There are exceptions to the orthodoxy in Western philosophy. For example, it’s pretty clear to me that Hegel is a dialetheist, although a number of Hegel scholars would disagree with that. But most Western philosophers have assumed that no contradictions can be true. In the Eastern philosophical traditions, the views are much more mixed. Some people subscribe to it, some don’t. But in the West, this orthodoxy has been so great that very few philosophers have tried to actually defend the view. There’s a defence in Aristotle’s Metaphysics, and most Western philosophers have assumed that Aristotle settled the matter. So, it doesn’t need another justification. An obsession, that is perhaps a bit strong, but the principle has been held to be so orthodox, so obvious, that it hardly needs a justification.

In Germany, refugees will be denied a residence permit if they give a supposedly contradictory account of their biographies or the route they took to get here. Contradictions do have a very real impact on our lives. What if dialetheism was the new orthodoxy?

That’s an interesting question. Look, the fact that some contradictions are true, and maybe plausibly so, doesn’t mean that any contradiction can be plausibly seen as true, right? And I think probably most of the time you meet contradictions in ordinary life, the thought that they’re dialetheias doesn’t have much plausibility. To believe that something is a dialetheia, there have to be good reasons. If you were to point out that what Trump has said is contradictory and ask him what grounds he has for the truth of what he’s said, he’s not going to be able to give you a very good answer.

Instead of instantly thinking of a contradiction to be false, people could keep the possibility that it could still be true in the back of their minds when they come across one – and thus react differently to it.

Yes, I think that would change one’s attitude to a certain extent. Normally, if someone commits themselves to contradiction, you would say: That can’t be right. There must be something wrong. If you’re a dialetheist, you’re going to say: Well, maybe what you say is implausible, but justify it for me. So, you’d be a bit more open-minded. But you still need a justification.

Do you think we would be better off as a society if everyone was a dialetheist?

I think generally we’re better off if we’re open-minded. But in practical terms, life is short, and you can’t ask people to justify everything. At some point, you have to accept that something is either plausible or implausible. There’s always a question of where you stop in that. (That’s a question of practical rationality.) And that’s always going to be the case, whether you’re dealing with contradictions or anything else.

In one of your books, Capitalism – its Nature and its Replacement (Routledge 2021), you write that questions concerning logic are much easier compared to the question of how to make the world a better place. Why is that?

When questions of logic become philosophically contentious, you may not be able to give an argument that everyone will agree with – it’s philosophy after all. However, it’s clear what kinds of arguments are relevant and what might settle matters. With the political problems we now face, it’s not like this. Take the question of global warming. It’s not rocket science that we’re in a mess, okay? We could go on the way we’re going, and life will become very difficult for many people. I don’t think that’s contentious. If we’re not stupid, we’ll make changes. How do you make changes in such a way that we improve things and not too many people suffer in the process? To understand that you have to grasp the root cause of global warming and how you might dismantle it. Now, those are very tough questions. I think any answer for them is going to be very contentious, and I’m not sure I know the answers, precisely because we’re dealing with very complex situations. I mean, to what extent is capitalism involved in global warming? I think the answer to that is that it’s really, deeply involved. But many hold that capitalism is not involved essentially at all.

There’s another comment you make in the same book, where you reference the dedication of your first monograph, In Contradiction (Oxford University Press 1987). It reads »To the end of exploitation and oppression in all its forms and wherever it may be.« And you write that despite the dedication, one doesn’t find much to this end in the book.

Yes, and I think that that’s true.

Then logic does not really play a part in making a change?

In In Contradiction, there’s very little discussion of political philosophy, right? Even though, when I wrote the book, I wanted to dedicate it to something. And I did want to dedicate it to making the world a better place. But I don’t claim there’s anything much in that book that will do so. The capitalism book is different. I mean, that really is me trying to say something about how I think one might go about making the world a better place… but there’s not much logic in the book – formal logic that is. Certainly, dialetheism plays no significant role in that book.

In order to analyse capitalism, you use Marxist theory according to which capitalism is usually understood to be a system that is in some sense contradictory in itself. Isn’t there a connection to the field of logic?

Some people have said to me, hey, you’re a Marxist, aren’t you? I say, yeah, sort of. And they say, well, Marx was a dialectician, dialectics involves contradictions. So surely, there must be a connection. My reaction then is: well, maybe, but when Marx and his followers, like Engels and Lenin and Mao, talk about contradictions, they often don’t really mean what a logician means. By contradictions, they mean tensions or conflicts of some sort. What Marx is pointing to in the passages in question is accurate enough, but it’s not what a logician would call a contradiction.

Your book on capitalism is different from your usual publications. How does it relate to your other works?

You know, in some sense, the capitalism book is the most important book I’ve ever written because it deals with problems that involve everybody in their lives, and I can’t say the same about most of the logic or metaphysics books I’ve written. The problems I deal with there interest me, but they don’t deal with issues that are fundamental to people’s lives. In that sense, the capitalism book is my most important book. It’s also the most frustrating book I’ve ever written because I realised how difficult these problems are, and I don’t even really have any solutions that satisfy me. I tried to address the problems as best I could, but I don’t pretend to know the answers. I don’t think anybody does. The capitalism book was really an attempt to open up a discussion to think about these issues and make progress on them.

A lot of people I talk to concern themselves with the future of this world. They tend to be quite worried.

The reaction I always get when I teach this stuff to people in their 20s is one of despair. A lot of my students have said to me: Yeah, the world is in a complete mess, and we don’t know what to do about it. I understand that reaction completely, but I think falling into despair is, though understandable, not the right reaction. The right reaction is: Yeah, the situation is tough. Let’s work hard to figure out a solution. Sorry, I didn’t mean to preach.

No worries. If we are not using logic to end capitalism, then what is it? How can we »move the world to a better place«, as you put it in your book?

Well, that’s a really hard question. Look, I don’t think dialetheism will be of much use in making the world a better place. Certainly, you need logic in some ways. I mean, you need to try to persuade people that things they are doing are crazy, okay? And that we could do things much better. And if you’re trying to argue then – hopefully – you’re going to argue sensibly. In that sense, you’re using logic. But to make a change, you’ve got to dismantle various power structures. That’s hard. They’re grounded in ideology, especially capitalist ideology. So, those are things you really have to attack. Logic, and by that I mean arguing, is going to play some role in that. Education is going to play an essential role in that. But you’re never going to persuade people of these things simply by using logic. You’ve got to dismantle the organs that produce ideology and the way they function.